Open Archief 3 featured artists Alice Wong & Simo Tse, Remco Torenbosch and Daria Kiseleva. The participants used the open digital collections of Nieuwe Instituut, Sound and Vision and the International Institute of Social History to create a new media work in which artistic research and the creative process are central.

Alice Wong & Simo Tse

Voices and Breaths

Voices and Breaths is an audiovisual installation based on Snelle Berichten Nederland-China [Quick Messages The Netherlands-China], a Cantonese-language radio program about Dutch news and current affairs that was broadcast between 1990 and 2008. The main goal of the program was to make it easier for Chinese-speaking migrants to bond with members of their own community and build a bridge to Dutch society. The radio program was forced to end production in 2008 when the NPS (Dutch broadcasting foundation) stopped financing all non-Dutch-language programs. In retrospect, the program can be seen as an example of changing attitudes towards migrants, specifically the Dutch-Chinese, in both the decision-making class and among themselves.

During their research Wong and Tse came across a private collection of cassette tapes with recordings made by one of the former radio presenters. On the recordings you can hear him speaking and listening, as if he is trying to find his own voice. The comparison between institutionalised archives and this personal collection provides interesting insights into how stories can be recorded and retold.

Remco Torenbosch

Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914 – 1966)

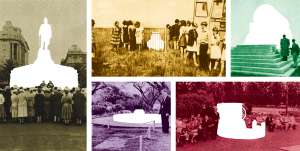

Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914 – 1966) is a work that focuses on the history of the Indonesian communist party PKI. It was founded during the Dutch colonial period by the Indonesian national movement and the socialist movement in the Netherlands. With this work, Torenbosch attempts to re-archive this history, that is scantily archived in the Netherlands, as extensively as possible. His efforts underline how the socialist movement and the political party, each with a strong anti-colonial political program, contributed to Indonesian independence in 1945, and the years that followed. The PKI arose from a collaboration between Semaun and Raden Darsono Notosoedirdjo from Indonesia in addition to Henk Sneevliet and Adolf Baars from the Netherlands. Their main goal was to achieve an independent Indonesia, international solidarity, and to realize reparations for the Indonesian population from the Dutch state. The party was banned from 1927 to 1945 but later became prominent in Sukarno’s state ideology. In the years that followed, the PKI became the largest non-governing communist party in the world, until its violent dissolution in 1965-66.

In this work, Torenbosch sets out to create an image bank of digital images from archives in Indonesia, the Netherlands and other parts of the world, resulting in an image report representing both local and international contexts. The image bank reveals the active history of the PKI, and also the international political forces, which exerted constant pressure to intimidate or prohibit the party. The image bank Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914 – 1966) will eventually be available to the public.

Daria Kiseleva

Haunting Futures

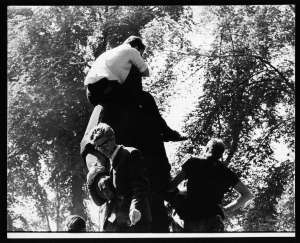

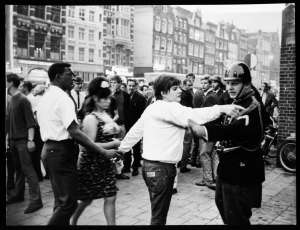

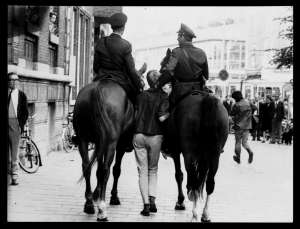

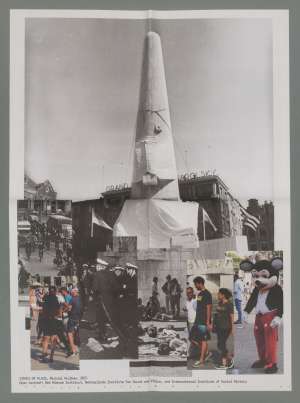

Kiseleva’s video installation examines how, in the archives, imagination is reflected in utopian ideas, political fantasies and carnival celebrations. It traces the ‘haunting’ futures inside the archives and examines their material manifestations in social reality and political and cultural thought. With this, Kiseleva explores the connection between utopian ideas and social movements. By juxtaposes idealistic, modernist utopias with marginalised, feminist utopias, she speculates about whose imagination counts and whose doesn’t. The work reflects on the history of imagination from the early modern period until today, and on how power structures have tried to censor and control it. The videowork is based on documentation of carnival celebrations in the Netherlands, as an expression of the subconscious imagination and popular culture.

Kiseleva positions carnival between aesthetics and politics, utopia and commercialised enjoyment, role reversal and the status quo, and a space of emancipation and conservative tradition. By mirroring the sci-fi horror genre, which, as philosopher Rosi Braidotti says, is “ideal for depicting states of crisis and change, and for expressing the widespread anxiety of our time,” it blurs the lines between fiction and reality.

Providing open access to digital, royalty-free collections provides institutions and makers with opportunities to discover new and surprising narratives. Together with the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision and the International Institute of Social History (IISH), Nieuwe Instituut has organised the second edition of Open Archief, a programme that stimulates the creative reuse of digital heritage collections. Three artists – Jessica de Abreu, Michiel Huijben and Femke Dekker – have explored the three institutions’ archives guided by the theme RE:SEARCH. Moreover, the artists’ choice of socially relevant themes such as racism, discrimination, activism and democracy make it all the more urgent for heritage institutions to open up their collections in new ways. The three participating institutions are responding to this challenge through Open Archief.

Jessica de Abreu

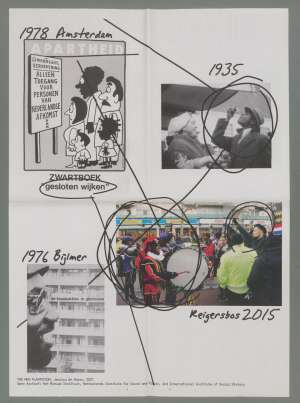

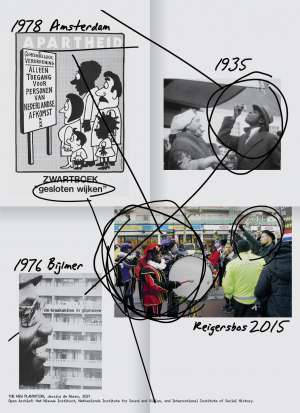

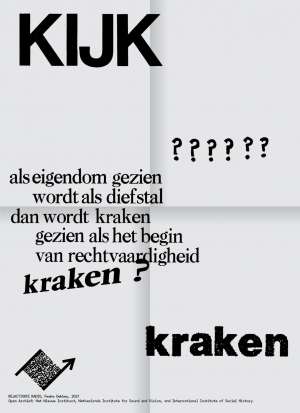

The New Plantation

De Abreu’s project The New Plantation presents ‘counter-images’ that show that black people are more than the colour of their skin, the history of slavery and the legacy of colonialism. Her work opens up the conversation about how racism and structural oppression affect our physical and mental health. The installation explores how old, vivid memories of slavery and colonialism and the ongoing reality of institutional racism evoke a variety of emotions that can trigger post-colonial depression: a mental state in which people are aware of the colonial past but realise that it is too late to do anything about it. While exploring the relentless history of racism, De Abreu also provides a personal commentary through memories of joy and laughter in a world that frequently denies black people pleasure.

Femke Dekker

RE:ACTIVATE RADIO

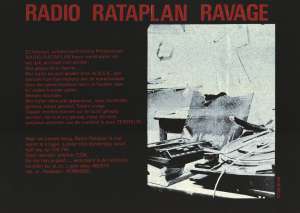

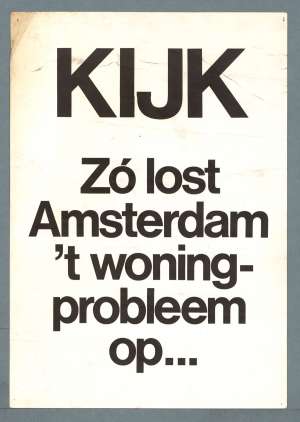

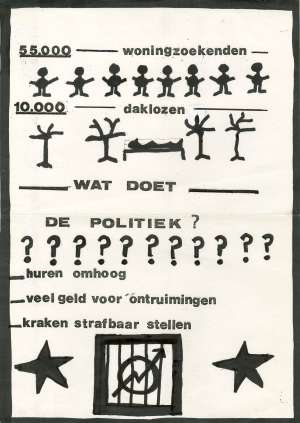

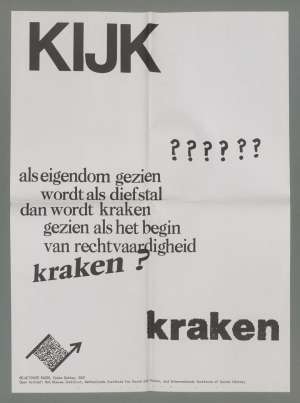

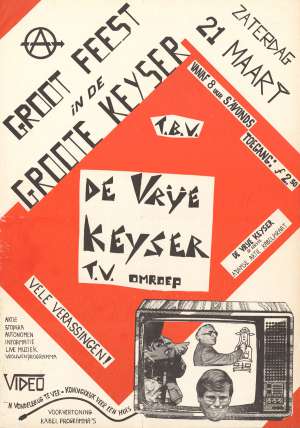

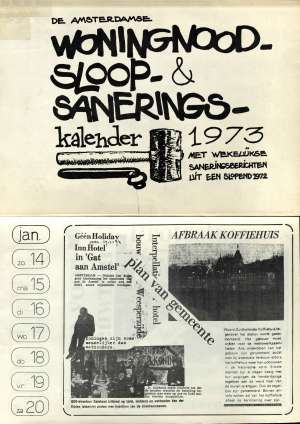

Femke Dekker’s project, RE: ACTIVATE RADIO, focuses on the reciprocal relationship between the media and activism. Activists have always made strategic use of the mass media as a platform to broadcast their ideas. This project explores the notions of both mediated activism and activist media.

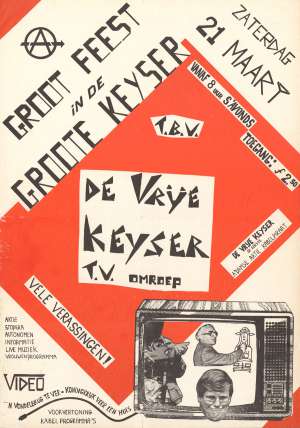

In the initial phase of her research in the IISH, Dekker came across the so-called ‘Staatsarchief’ (State Archive), the archive of the Dutch squatters’ and activists’ movement. It contains the vast audio archive of Radio de Vrije Keyser, which began broadcasting on 13 January 1980 from De Groote Keijser, a complex of six squatted buildings on the Keizersgracht in Amsterdam.

The archive appeals to Dekker’s interest in counterculture and represents radio’s ability to function as a call to action and as a tool for community building. In this respect, the topics discussed in the historical radio broadcasts, such as gentrification, the housing shortage and the need for grassroots activism, are just as relevant today.

In addition to providing access to Radio de Vrije Keyser broadcasts, Dekker is also producing four radio programmes that will be broadcast on the online station Ja Ja Ja Nee Nee Nee. These broadcasts reflect on the materials that Dekker has found and address the positions of the archivist as activist and the artist and activist as archivist.

Michiel Huijben

States of Place

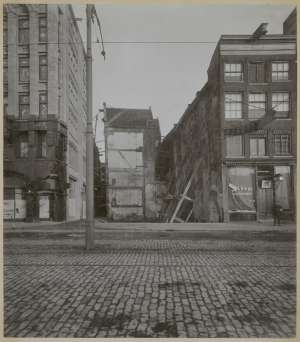

Michiel Huijben searched the three institutions’ archives for images that reveal the role of public spaces in society. His search for places rather than events reveals a complex picture of the kinds of activities that are permitted in public spaces. The Dam Square in Amsterdam and the Malieveld in The Hague play a central role in the work that Huijben has created. Because physical access to the archives was the limited by the coronavirus pandemic, this year the archival research was conducted mainly online and was therefore limited to digital images of original archival materials. This experience was decisive for Huijben’s research and he has incorporated it within his installation for Open Archief. The work combines images from three archives with material found on the internet, and considers these as a whole to create a more complete picture of the public realm while simultaneously questioning the authority of ‘The Archive’.

Open Archief hosted an International Symposium that took place in the spring of 2021. It was a multidisciplinary event that aimed to bring together professionals from various fields (image makers, artists and professionals in the field of heritage and copyrights) and that shared knowledge and insights on the topic of artistic reuse of heritage. The aim was also to present this knowledge to a wider audience and had it critically assessed by these professionals, interested parties and institutions. The symposium was made possible through the financial support of Pictoright.

The re-use of digital collections in museums and archives generates new narratives with potentially surprising and innovative forms. In 2019 Nieuwe Instituut and the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision invited three media artists to create new works based on the institutions’ digital collections; artist Guy Königstein, filmmaker Donna Verheijden and artist/designer Oana Clitan have each developed a media artwork that was exhibited at Nieuwe Instituut in November 2019.

Open Archief invites media makers and heritage organisations to debate the importance of creative reuse of heritage and the accessibility of online collections. Through an open call, three makers were selected to experiment with the possibilities of digital heritage collections in creative, technological and copyright-related ways. The expertise acquired through this talent development process was shared with makers and heritage professionals in various ways.

Oana Clitan

Future news, official screen

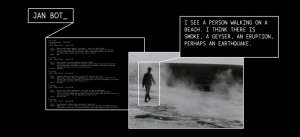

In her project, Oana Clitan used the rhetoric of historical and current news broadcasting to speculate on how information will be presented in the future. The installation explores a scenario in which electrical devices are all damaged, so that it is impossible to produce new visual content. The only means of visual expression in this world is through scarce, salvaged archival material, which the government uses to inform citizens about the latest developments in the crisis.

Guy Königstein

Dear past, what would it take to throw you off balance?

An installation with photographs and film with spaces seemingly frozen in time, silent meeting rooms, empty staircases, dusty shelves, long corridors and closed doors. These materials provided the stage for uninvited visitors. Guy Köningstein assumed the role of one unexpected guest or harmless intruder, wandering through the archive’s maze in search of connections and ways of belonging. Opening drawers and files, he asked the question: ‘Dear past, what would it take to throw you off balance?

Donna Verheijden

The Stolen Archive

The Stolen Archive was a speculative thriller. The video installation by Donna Verheijden makes connections between the stories and events hidden in the archives of Nieuwe Instituut and the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision. Verheijden draws upon the collections as repositories of images, audio clips and objects that can be used as characters, props and sets.

For an overview of last year’s edition, click on this video by Marit Geluk.

A digital publication about Open Archief 2019 is available here (desktop version, Dutch only).

Open Archief is a multifaceted, collaborative project that explores the potentials of what can be inspired by making archival material accessible to artists for creative reuse. it was initiated by three Dutch heritage institutions: Nieuwe Instituut, Sound & Vision, and the International Institute of Social History. Open Archief urges and supports media artists to make use of digitized and open archival collections. Open Archief brings media artists and heritage institutions together to discuss the importance of creative reuse of heritage and of making digital collections available.

After three editions of residencies and clinics, the project team sought a way to showcase the outcomes of the various aspects of the Open Archief programme in a more concrete way: a bundle of essays, for which we partnered up with Stichting Archiefpublicaties (S@P)and the Pictoright Fund. The team invited artists from their networks to contribute an essay on how they use and/or see the role of archives in their work.

Through three open calls, media artists were invited to create new work using archival material from the digital collections of Nieuwe Instituut, Sound & Vision, and the IISH. The selected artists worked closely with the collection experts from the three institutions for at least six months and their work was exhibited at Nieuwe Instituut.

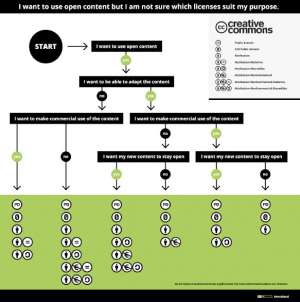

Re:Use Clinics are workshops and presentations which invite archival institutions and artists to discuss the use of archival material. How do we create an open digital environment that enables the artistic reuse of heritage materials? How can artists take advantage of public domain archival materials? What are possible pitfalls? These and more are the questions we focus on.

Sound & Vision is one of the largest media archives in the world, it stores various types of media, such as radio and television programs, video (games), written press, political prints, gifs, websites and objects. Sound & Vision is one of the institutions which aims to objectively map the Dutch media landscape and highlight current developments from a media-historical perspective. The collection of the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision contains more than 1 million hours of cultural-historical, and audiovisual material. A large part of the collection is made available by Sound & Vision under open licenses. The public collection currently contains tens of thousands of items of audiovisual material and is available for creative reuse by third parties. This is also the case for the Open beelden platform.

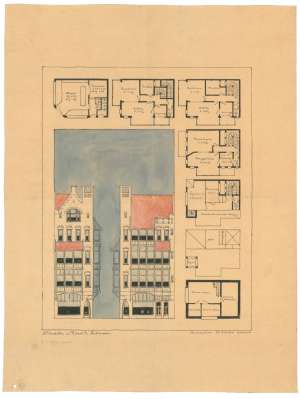

Nieuwe Instituut focuses on major developments in society, such as the housing shortage, the climate crisis, and the emergence of artificial intelligence. Designers, including architects and digital creatives, make an important contribution to these developments. Nieuwe Instituut shows the work of designers, brings people together, and collects, develops and shares knowledge. Nieuwe Instituut looks after the past of the design sector. The National Collection of Dutch Architecture and Urban Design is one of the largest architectural collections in the world, with some four million drawings, models, photographs, letters and digital files. In addition, the institute works in a network context to preserve design archives and archives in the field of garden and landscape architecture. The collection is used for research and exhibitions in the Netherlands and abroad. The architecture collection can be consulted online or in the Research Centre, which is open to the public.

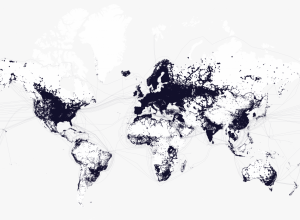

International Institute of Social History focuses on labour and social movements across the globe over the past five centuries. We provide sustainable access to information, examine the relationship between work and social inequality and collaborate with societal groups.

Graphic Design: Marius Schwarz

Web Development: François Girard-Meunier

Data policy and cookies

This website might use cookies placed by third parties in order to display embedded contents. Examples include (image) material that is loaded via another website, for example, a YouTube, Vimeo or Soundcloud content element. These cookies are only placed after your consent has been collected. When your consent is collected, a functional cookie is created for saving these preferences for convenience.

This website uses Matomo Analytics in order to collect anonymized basic information about website visitors in a cookieless manner (learn more). This anonymized data is stored by Nieuwe Instituut on EU-based servers, according to European Law (GDPR, General Data Protection Regulation).

This website is hosted and managed by Nieuwe Instituut. Read more about Nieuwe Instituut’s general privacy statement.

‘Open Archief – Artistic Reuse of Archives’ holds 12 essays, created by artists, curators, and researchers. The book follows three editions of the programme Open Archief (2019-2022), a multifaceted collaborative project that explores the potentials of what can be inspired by making archive materials accessible to artists for creative reuse. With contributions by Philipp Gufler, belit sağ, susan pui san lok, Paula Kommoss, Gill Baldwin, Jessica de Abreu, Pablo Núñez Palma, Michiel Huijben, Pieter Paul Pothoven, Elki Boerdam, Shock Forest Group, Femke Dekker, Alice Wong and Simo Tse. Initiated by the Nieuwe Instituut, Sound & Vision, and the International Institute of Social History. In collaboration with Stichting Archiefpublicaties (S@P)and the Pictoright Fund. Edited by Eline de Graaf, Michael Karabinos, Thijs van Leeuwen, Cees Martens and Marius Schwarz. Designed by Marius Schwarz.

With this book, we want to paint a picture of archival reuse by artists and how they relate (themselves) to archives and archival institutions. In doing so, we firstly want to demonstrate to the archival community, and anyone else, that archive reuse is co-creation. Secondly we intend to inspire readers to actively choose to work with archives: the essays in this publication provide many examples and avenues to explore. Finally the book is aimed at a wider audience interested in art and archives. We hope to offer insight into the dynamics at play between ‘archive’ and user.

The book is freely available online via Sound & Vision Publications.

A printed edition is for sale.

In his article Of Other Spaces, Michel Foucault talks about certain places in cultures, that exist and are formed in the very founding of society, something like counter-sites, effectively enacted utopias, within which all the other sites are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. He calls them heterotopias. As opposed to utopias, that are, effectively, sites with no real place, the location of heterotopias can be indicated in reality. Describing different types of heterotopias, Foucault speaks about libraries, museums and archives as spaces “in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit. […] Opposite these heterotopias, there are those linked, on the contrary, to time in its most fleeting, transitory, precarious aspect, to time in the mode of the festival.”[1] An archive and a carnival can be seen as representations of these two different types of heterotopias, in their contrasting relation to time. One of them is an immobile place of perpetually and indefinitely accumulating time, whereas the other one can only exist in its fleeting temporality. But both of them are microcosms, containing a world within a world, mirroring, inverting and subverting the ‘outside’ reality.

Archives are often seen as carefully curated collections, metaphors for a collective consciousness. But they also can be seen as ‘cabinets of curiosities’, where through systems of organisation, certain perceptual frameworks are revealed, and worldviews are constructed. They substantially contribute to the creation of meaning and knowledge, they project a certain accumulated worldview onto society and the future, becoming its foundation. In order to understand an archive better, we can ask questions like: Why does this archive exist? Why does it contain this item rather than another? And what is missing from the archive? After all, who decides what goes into an archive? Historically these decisions have been gendered and centred on particular ideas about what and who matters in history. Archives are always partial and biased, never complete. They are epistemological moments, rather than passive collections. The moment the objects are being archived they become frozen in a fixed position and order. As Jacques Derrida famously said in Archive Fever: “[The] technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future.”[2] Memory is not a storage, it requires constant reflection to keep it alive. Power is at the centre of archival work: it has the power to retain, the power to discard, the power to partially shape what is remembered and how. What do institutions remember? What do they forget? Archives are filled with gaps and silences. Being archived can prove your existence, but can your absence from the archive indicate the opposite? Another question that can be asked is, can archives be a space for envisioning a different future?

Archives undoubtedly have a strong influence on the future, as a resource for knowledge production and projection of certain worldviews. They also often contain a repository of possible futures, of yet to materialise realities, “historical alternatives that haunt a given society”[3] in the form of utopian ideas, political imaginaries, alternative communities, technological innovations and artistic and architectural projects. They can all be seen as a manifestation of different forms of imagination. Working with the archives of the International Institute of Social History (IISG), Beeld en Geluid and Nieuwe Instituut, I was interested to reflect on how manifestation of these ‘haunting futures’ influence construction of social reality and cultural and political thought. Who has the right to imagine them? And is it at all possible to think about future outside of anxiety that surrounds it?

The myth of the future, as a cultural construct built around the notion of progress, spacial idea of expansion, advancement of economy and knowledge, is rooted in the early modern period and the emergence of modern capitalism and the colonial era. The current state of a disillusionment in the future and the inability to imagine an alternative to capitalism, can be understood as a cultural logic of advanced capitalism. The future doesn’t appear to be an object of choice and a collective conscious action, but an inevitable catastrophe. To quote Rosi Braidotti: “The contemporary imaginary is impoverished and unable to think about difference outside of frame of deep anxiety.”[4] The continuous war against imagination, which according to David Graeber, “is the only war capitalists have managed to win,”[5] led to the widespread death of political imagination. And the bureaucratic and financial apparatus, created to general perpetual hopelessness, destroys any sense of possible alternative futures and shreds human imagination.

When I first started my research in the archives, I began to explore how imagination was expressed in them. In my previous research I was interested in the history of imagination as an internal sense, playing a key role in mental function, and having the power to influence reality, its political potential and subsequent censorship and control, as well as its relation to vision and representation. Working with the archives, I wanted to reflect on the power of imagination and its political dimension, on the right to imagine in the context of contemporary lack of social and political imagination, and the inability to envision a world, different from the one we currently live in. I wanted to observe the connection between memory and imagination, past and future, as they are embodied in the archives.

I began to explore the utopian collection of IISG, in order to reflect on the relationship between utopian imaginaries and social movements. At the same time, I was also looking for different manifestations of ‘imagination’ and ‘future’ through examples of technological innovation, science fiction narratives, and modernist projects. When I came across documentation of carnival celebrations in the Netherlands in the archive of Beeld en Geluid, I found carnival to be a perfect metaphor for an enacted utopia and an expression of social and political imagination. Eventually, these different elements and thoughts came together in the film, in a juxtaposition of well-known political utopian ideas, modernist utopian architectural dreams and more marginal feminist utopian narratives.

Utopia.

Utopias afford consolation: although they have no real locality there is nevertheless a fantastic, untroubled region in which they are able to unfold; they open up cities with vast avenues, superbly planted gardens, countries where life is easy, even though the road to them is chimerical.

— The Order of Things, Michel Foucault, 1966

The power and impact various utopias had and are still having on reality is vast. There is a clear link between utopian ideas and social movements, and the collection of IISG is a great illustration of that connection. Their utopian collection contains books about imaginary travels, utopian communities and futuristic visions. It includes “contemporary editions spanning centuries of utopian thought and ranging from a very early reprint of More’s Utopia (1518) to works by Fourier, Saint-Simon, Cabet, Proudhon, and Owen.”[6] As one of the treasures of the collection, in a vitrine in the heart of the building, Thomas More’s third edition of Utopia is proudly displayed next to the manuscript of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. The works of utopian thinkers inspired social movements, utopian experiments and alternative communities. Is there still potential in utopian thinking? Can it have a politically energising perspective? Can it be a radical act of philosophical speculation? One undoubtedly positive element in utopia, is that through it, the reader gets infected with the possibility of an alternative. Utopian vision of a better society relies on the engaging of imagination to see the possibilities. There is a power in seeing something that you can’t ‘unsee’. It makes you understand that the alternative is possible. The ‘naturalness’ of the world gets disrupted.

Utopian ideas are present in myths, religions and imaginaries of many cultures. But the concept of utopia is considered to be a by-product of Western modernity, with Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) being its starting point. This book is “almost exactly contemporaneous with most of the innovations that have seemed to define modernity (conquest of the New World, Machiavelli and modern politics, Ariosto and modern literature, Luther and modern consciousness, printing and the modern public sphere)”.[7] Throughout the time, utopia went through multiple transformations, and the relationship towards it kept changing. In each utopian narrative historical conditions of possibilities of these peculiar fantasies were revealed.

The questions about the practical-political value of utopian thinking and the identification between socialism and utopia, continue to be unresolved. The classical criticism of the utopian impulse is that it is impossibly distant. Utopia is anywhere but here and now, it is alternatively the ‘good place’ (‘eutopos’) and ‘no place’ (‘outopos’). But more importantly from its very origin it is based on brutality and coerced from above. To quote Ursula K Le Guin: “Every utopia since Utopia has also been, clearly or obscurely, actually or possibly, in the author’s or in the readers’ judgment, both a good place and a bad one. Every utopia contains a dystopia, every dystopia contains a utopia.”[8] Like in the case of Thomas More’s Utopia itself, which on the one hand denounced private property and advocated a form of communism, on the other hand was originally built by a tyrant Utopus on colonisation of the “uncivilised inhabitants” and creating an artificial island by “bringing the sea around them”.[9]

“There were good reasons to distrust and even dismiss the term ‘utopian’, although […] the main problem was not idealism and futurism, but rather the term’s deeply racialised historiography and narrow set of literary, aesthetic, philosophical, historical and sociological references.”[10] Feminist utopian and science fiction writers embraced the potential of the utopian genre, even though feminist utopias were quickly dismissed and moved to the margins of the discussion, into its own subfield, as a result of the the effects of structural violence on the imagination. Feminists were critical of closed-ended, top-down utopias depicting static perfection with no room for development, that rely on rigid hierarchies and coercion to maintain this order. Instead of projecting a totalising idea, feminist utopian speculative fiction, deals with imagining the future, building on the critique of the present and past. This type of the utopian writing is often also referred to as SF, which, as Donna Haraway describes it, “is that potent material-semiotic sign for the riches of speculative fabulation, speculative feminism, science fiction, speculative fiction, science fact, science fantasy—and, […], string figures. In looping threads and relays of patterning, this SF practice is a model for worlding…”[11]

Carnival.

I believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience which would be the mirror.

— Of Other Spaces, Michel Foucault, 1986

Carnivals, as much as mirrors, are real spaces that contain a ‘parallel’ world. They are enacted utopias, that can only exist in their fleeting temporality. Following the template of utopia and dystopia, heterotopia (Ancient Greek: hetero - other, another, different; topos - place, which can be translated as ‘other, different place’ or ‘a place of differences’) is a parallel space mirroring and yet upsetting what is outside. Heterotopias can be seen as spaces that make room for something politically experimental. They are spaces of and for the imagination. Foucault calls for a society with many heterotopias, not only as a space with several places of/for the affirmation of difference, but also as a means of escape from authoritarianism and repression. When I came across videos of documentations of carnivals, I saw them as a great example of a heterotopia—a microcosm, a space where imagination seemingly runs wild… A ‘reimagined’ space that at the same time allows for imagination to manifest itself. A bodily expression of a utopia.

Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy ‘syntax’ in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to ‘hold together’.

— The Order of Things, Michel Foucault, 1966

Early on, carnivals were recognised as having potential to be one of those ‘disturbing’ spaces, where norms and categories could be questioned and challenged, and status quo suspended. The theory of carnival as a transgressive act of political resistance is generally said to have been pioneered by the Soviet structuralist Mikhail Bakhtin. In his study of Rabelais’s work, Bakhtin presented medieval and Renaissance carnival as a festive critique, through the inversion of binary semiotic oppositions, of ‘high culture’. This analysis contributed to carnival being conceptualised as a ritual of rebellion. “To Bakhtin, however, carnival did not simply consist in the deconstruction of dominant culture. It also eliminated barriers among people created by hierarchies, replacing them with a vision of mutual cooperation and equality. […] On a psychological level, it generated intense feelings of immanence and unity—of being part of a historically uninterrupted process of becoming. It was a lived, bodily utopianism, distinct from the utopias deriving from abstract thought, a ‘bodily participation in the potentiality of another world’”.[12] Bakhtin’s work was foundational for the field of ‘carnival studies’, which emerged in the 1970s as a combination of cultural history, anthropology, and sociology.

Carnival parades with large floats are a superabundance of symbols and meanings, a spectacle, an exhibition, a flow of monsters, fanciful characters and jokers. Many parade themes tell a visual story of recent events. It was also a custom during carnival that the ruling class would be mocked using masks and disguises. The combination of political protest and colourful party exploits the ambivalent position of carnival, between aesthetics and politics. Throughout the history of the carnival in the Netherlands, there were various moments of censorship, when either the church or the state were trying to prohibit it altogether or censor certain topics and representations. A new morality was tested, to see what was allowed. And while certain subversive types of behaviour were allowed, the total freedom and anarchy were not welcome.

“Carnival spirit with its freedom, its utopian character oriented toward the future, was gradually transformed into a mere holiday mood,” Bakhtin concluded.[13]

“By the mid-nineteenth century the change was complete: carnival culture had been relegated to the sentimental realm of folkloristic survivals.”[14] As a result of domestication, commercialization, political co-optation, aestheticization, traditionalization and institutionalisation, carnival has lost its political potential having transformed into a space of escapist fun in the form of mainstream entertainment. It has transformed into a space that reproduces hierarchies, power structures, and misrepresentations of the world they mirror, where strong sets of guarded traditions and practices often stay exclusionary, perpetuating racism and gender stereotypes.[15]

New Babylon.

Daria Kiseleva, Haunting Futures, 2022.

The question if the nature of carnival is inherently transformative and subversive, or fundamentally conservative, divides the opinions of the scholars. Some researches see carnivals as a form of social control, arguing that its ritualised, periodic nature serves as a mechanism to dissipate revolutionary energy and maintain the status quo. Others see a possibility of carnivals to create a space for renegotiating and resisting hegemony. The rebellious potential of carnivalesque—“as a medium of emancipation and a catalyst for civil disobedience”[16]—was embraced as a cultural practice and instrumentalised during the protests by the global anarchist movement.

The element of carnivalesque was already previously used and advocated for, by the members of the Provo movement (1965-1967), as a way of provoking the authority through a playful action, in which uselessness and voluntary unemployment were contrasted with authoritarian morality. Carnivalesque, or a playful action, was also close to the philosophy of the dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhyus, whose “architectural science fiction”[17] project New Babylon (1956-1974), can be seen as an ultimate modernist utopia, based on an idea that it is possible to escape an unfree world by achieving full automation. Describing the future population as homo ludens, Constant imagined the world wide city of the future, in which the need to work is replaced by a nomadic life of creative play, a modern return to Eden. “Deeply rooted in the tradition of the avant-garde with the desire for the renewal of society, New Babylon offers a challenging proposal of a network of enormous multilevel interior spaces spreading so as to eventually cover the planet…”[18] Architecture and urban planning have always played a vital role in the utopian imagination. By the early modern period the promotion of city planning and the design of urban spaces became a means of creating and maintaining social control in utopian plans and fantasies. In More’s Utopia the world consists of uniform towns that are geometrically organised, creating an infrastructure that supports the discipline of the inhabitants. Idealised urban spaces are described in Francis Bacon’s description of Bensalem in New Atlantis (c. 1624), Charles Fourier’s phalanstère buildings and Robert Owen’s proposed communities of the early 19th century.

New Babylon contained in itself both an extreme artistic and architectural plan, and the element of carnivalesque, or playfulness, that formed his ideological vision of the construction of a ‘new man’—homo ludens. The utopian vision of liberation through play and creativity is manifested in a total abstract vision of one man, through homogenisation and elimination of differences. But New Babylon, isn’t a safe space, according to Constant. Instead it is a space of conflict. And the liberated through creativity homo luden is not liberated from aggressively and violence.

“Eventually, Constant foresaw the destructive part of his proposed environment, since the last of his drawings lay bare a site of violence and terror”.[19]

Imagination.

What revolutionaries do is to break existing frames to create new horizons of possibility, an act that then allows a radical restructuring of the social imagination. This is perhaps the one form of action that cannot, by definition, be institutionalized.

— Revolution in Reverse, David Graeber, 2011

This uniformizing ideal of progress, as it moved the western world away from nature, blinded us to the immanence of life. It also alienated us from the different futures that were not in line with the Enlightenment ideals. It is these alternative future scenarios that are becoming more feasible and necessary in the era of the Anthropocene, and which are emerging as new paths of becoming.

— Philosophy after nature, Rosi Braidotti, 2017

Imagination has long been a subject of philosophical debate and its power had been widely recognised. Studies in the history of imagination explore ideas about the physical force of imagination as it was understood in the early modern period. Imagination (or Phantasia) “lodged between sense perception (the realm of the objective) and memory or mind, or soul, processes perception”,[20] by means of images. Socrates likened the impression of images in the mind to imprinting seals in wax. In the period of early modernity images (in early natural science atlases) gained the power to stand for what they represented, becoming truthful records of their subjects. At the same time imagination started to be seen as one of the internal senses, playing a key role in mental function, according to the early modern medico-philosophical theories, and having the power to influence reality, forming an image-based model of cognition. Descartes attributed to imagination yet another role: an act of the will, that connected it to the practical, ethical and political dimensions of human life. It was understood that the inability to control imagination could amount to a threat to social order. What is produced in the imagination can be dangerous and subversive. Multiple thinkers warned against the dangers of imagination and the necessity to control it. Amongst them was Hobbes, who in his political treatise Leviathan (that is also often suggested to be a utopian work) posited that in order to “ensure social unity, peace and political stability, the sovereign must maintain his subjects in the state of ‘political sleep’, preventing any kind of new inputs from disturbing their imagination and by establishing a strict regime of censorship in order to combat and silence any alternative imaginaries”.[21]

An alternative understanding of imagination was proposed by Spinoza, for whom it consisted in the awareness of the bodies before us, and an individual was seen as a constitutively interdependent being, produced through and productive of its relations with other individuals. “… for Spinoza the life of the mind, and so of imaginative life, is also the life of the body. This is the first sense, then, in which imagination, as a way of thinking, is also a way of existing”.[22]

Drawing from Spinoza’s understanding of imagination, as a more embodied, relational and interdependent experience, imagination can be seen as a social praxis, as a continuous process of reinvention of the self “on a basis of what you hope you could become”,[23] and re-conceptualisation of normative categories and social, cultural and political constructs. Imagination is based in the present, drawing inspiration from past struggles and ‘alternative futures’ to work on the present, “actualising the virtual possibilities which have been frozen in the image of the past [24]. The tense that best expresses the power of the imagination is future perfect. This is the tense of the virtual sense of potential. Memories need imagination to empower the actualisation of virtual possibilities.

From this perspective I looked at the archives as repositories of possible futures of the past. In thinking about the future there is a danger of detaching oneself from the present. Therefore, Haunting Futures is rather speculating how to inhabit the troubled present, by engaging with these ‘haunting futures’, as opposed to the idealistic visions and modernist ideas, dreaming of creating a clean slate by means of destruction of the past. The film itself, just like the carnival, is a heterotopia, akin to a mirror, containing a real and a fictional image at the same time. It is both a science fiction horror and a documentary where the ghosts of the past and present come alive. It is in a constant flux, opposing the binary logic, creating a space of confusion and disrupting the possibility of a historicising logic.

His name is Chow Yiu-Fai (b. 1961, Hong Kong) and he was also given the English name John. For close to ten years, he was a radio hosts of Snelle Berichten Nederland-China, a Cantonese-speaking programme funded by the Dutch government, which was broadcast from 1990 to 2008. Before that, he was an editor for a newspaper in Hong Kong, and after that, he became an academic in cultural studies, researching topics such as young Dutch-born Chinese, creative labour, single womanhood, and ageing. In Hong Kong, he is best known as a lyricist, an identity and a profession that he carries with him to the present day. Hosting the radio show was his first form of employment after moving to the Netherlands in 1992. Chow now resides in Amsterdam, in a 3-story house built over the basement where the writer Neel Doff (1858–1942) once lived. Growing up in poverty, Doff modelled for renowned Belgian painters, and had to work as a prostitute to support herself and her family. Her first book, Dagen van Honger en Ellende (1911), was later adapted for Keetje Tippel (1975), a film directed by Paul Verhoeven. Such anecdotes of personal narratives are all small insertions into the collective memory and the history of the Netherlands, and, albeit by chance, are nonetheless lyrical.

The idea for Voices and Breathes was conceived through inter-personal encounters, and the personal narratives of Chow became the main thread of our approach in archival research. The final installation consists of three soundtracks composed of fragments collected from the Beeld en Geluid archive, our interview with Chow, and his personal collection of cassette tapes. Through weaving together audio recordings from three time periods and sources, we, as a duo of an artist and a designer, attempt to portray our impression of a person who is talented and empathetic, and was a voice familiar to many migrants with Chinese heritage [1] living in the Netherlands.

While there were only 2.5 years (2002–2004) of digital recordings available to us through the Beeld en Geluid database, Chow’s personal collection of cassette tapes (1993–1999) gave us a broader overview of how the radio programme sounded and was structured over the years. Our in-person interviews (2021–2022), in hindsight, were used as a compass navigating through the many episodes of Snelle Berichten Nederland-China, layering them with first-person accounts of the inception and the eventual cancellation of the radio show.

Snelle Berichten Nederland-China was part of the “mother tongue” programming of NPS (Nederlandse Programma Stichting), which also broadcast in Moroccan and Turkish. In the pre-satellite-TV and early internet era, this was a civic commitment by the Dutch government to facilitate cultural integration among migrants into the broader Dutch society. Many first-generation, Dutch-Chinese migrants worked in hospitality or in jobs with long hours, which allowed very little room for entertainment and recreational activities. The radio programme became part of the audio background in their workplaces, living rooms, and kitchens. Operating at different durations and frequencies, the content of the programme was multivalent: translated Dutch and international news, social announcements, electoral and tax information, interviews, and radio dramas, as well as a phone-in segment [2] in which the hosts and the listeners discussed current affairs in the Netherlands and beyond. The programme was conducted in Cantonese, a language spoken predominantly in the Southern fringe of mainland China and in Hong Kong, but could be understood by members of Chinese diasporas at different localities. Listening back to the recordings in the present day gives an intimate understanding of the lived experiences and emotional inner-lives of Dutch-Chinese migrants from 2 decades ago.

The decision to utilise a single-person account, instead of a multitude of voices, was based on the “doubleness” of Chow’s character. Being a migrant himself, hosting a migrant-oriented radio show, we have positioned him as both the speaker and the listener. The project title Voices and Breaths is coined from the phone-in segment of the programme. The immediate exchange of speaking and listening between Chow and his listeners formulates a tête-à-tête: while their migrant experiences are echoing and also bouncing off each other, he is also accommodating his speakers by listening intently. To turn the microphone around, we have also included fragments from his own interviews on other radio shows, in which he becomes the subject of interest. While listening to the radio is less of a collective activity than watching the TV or films, it is common for radio hosts to address their listeners collectively. In Cantonese, the singular pronoun for “you” is different from the multiple. And this is the same in Dutch [3]. By following a singular you, the character of Chow was reconstructed as a duo; by omitting his listeners’ responses, we scripted a dialogue within himself. Poet and writer Ocean Vuong addressed the issues of identity, and he recognised that even though our curiosity should not be bound by it, we could not escape who we are and how we are perceived. “Even if I were to write the word ‘the’, t-h-e … that is still an Asian-American ‘the’,” said Vuong. The general observation about Dutch-Chinese is they are constructed as “model migrants” [4] and as a consequence of their lack of visibility.. Refusing to abstracting himself into a checkbox nor a category, Chow also asked the question: Waarom moet het zo? Ofwel, Waarom mag het niet anders? (Why does it have to be like this? Or why can’t it be otherwise?)

Audio recording omits as much as it contains. Without any visual clues, audio recordings appear to be more malleable than visual records. With Voices and Breaths, and its omission of visual elements, we want to bring our audience’s attention away from preconceptions. The soundtracks are mainly in Cantonese, sometimes in Dutch, and occasionally in English. If you don’t understand (any of) the languages, all you hear are voices, and perhaps breaths. And if you are patient enough, the bilingual subtitles are the only thing you can hold onto, an experience not dissimilar to that of a migrant arriving in a foreign country. The signifier of time can only be found in music: 2 Cantonese songs from the 1980s, and the Dutch song, 15 Milijoen Mensen (15 Million People). The Dutch population has now reached 17,5 million.

During one of our visits to the International Institute of Social History (IISG), one of the archivists described the archive as a fishbone: it may or may not include the end results (the fish’s head) but it collects strands of evidence along the way. We found that metaphor to be moving. We would like to think that artistic intervention is to bring movement to the seemingly static surfaces and logical organisation of archives. When it comes to treating a radio show as archival material, we have found that our encounter with archives, both digitally with DAAN and in analogue format with the cassette tape collection, feels more like glimpsing the shine of fish scales. From the recordings, the anonymity of the speakers and listeners who phoned and spoke on the show gives the tiniest amount of information about who they are, and in most cases, there was not enough time to dive into an informative discussion. The radio show could thus be treated as, in part, an archive of emotions and affects, ventilated by a generation of Dutch-Chinese migrants. To truly understand and reflect upon their lived experiences in the Netherlands requires much more research through the lens of historical, socio-economical, cultural, and gender perspectives. As artists and designers, working with archives is to reaffirm and to grapple with the impossibility of neutrality, as historian Edward Hallett Carr stated in What is History (1961), “no documents can tell us more than what the author of the document thought” and “only the future can provide the key to the interpretation of the past … It is at once the justification and the explanation of history that the past throws light on the future, and the future throws light on the past.” Again, our intervention is neither neutral nor formal; it was not our intention to be either. It was personal.

[1] The lineage of Chinese migration history in the Netherlands is centuries long. While the history of Indonesia is intertwined closely with its Dutch and Chinese counterparts, localities such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia also play a significant role in the concurrent trajectories of Chinese diasporas. The concept of diaspora challenges the idea of community which is often bound with homogeneity, such as place of birth, habitation, ethnicity, language, tradition, centre, periphery, and culture.

[2]The phone-in segment is called Tùhng Sēng T’ong Hei (Same Sound Same Breath) which refers to a Chinese idiom meaning like-mindedness.

[3] For instance, when one is addressing a single person, jij or jouw can be used, whereas jullie is used for a group of people. A similar logic can also be found in Cantonese.

[4] To name one example of many, Chow quoted from an article appearing in a major newspaper, De Telegraaf, asserting that Dutch-Chinese migrants are often considered to be hard-working, and trouble- and complaint-free.

Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914–1966) is a work that focuses on the history of the Indonesian communist party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, or PKI). It was founded during the Dutch colonial period by the Indonesian national movement and the socialist movement in the Netherlands. With Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914–1966), Torenbosch attempts to re-archive this history, so scantily archived in the Netherlands, as extensively as possible. His efforts underline how the socialist movement and the political party, each with a strong anti-colonial political program, contributed to Indonesian independence in 1945, and the years that followed.

The PKI arose from a collaboration between Semaun[1] and Raden Darsono Notosoedirdjo[2] from Indonesia in addition to Henk Sneevliet[3] and Adolf Baars[4] from the Netherlands. Their main goal was to achieve an independent Indonesia, international solidarity, and to realize reparations for the Indonesian population from the Dutch state. The party was banned from 1927 to 1945 but later became prominent in Sukarno’s state ideology[5]. In the years that followed, the PKI became the largest non-governing communist party in the world, until its violent dissolution in 1965-66.

In this work, Torenbosch sets out to create an image bank of digital images from archives in Indonesia, the Netherlands and other parts of the world, resulting in an image report representing both local and international contexts. The image bank reveals the active history of the PKI, and also the international political forces, which exerted constant pressure to intimidate or prohibit the party[6]. The image bank Partai Komunis Indonesia (1914–1966) will eventually be available to the public.

[1]

Semaun (1899 Curahmalang, Jombang, Dutch East Indies – 1971 Jakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia). In 1915 at the age of sixteen, he was elected as one of the first Indonesian members of the Union of Train and Tramway Personnel (VSTP), soon quitting his job as a railway worker to become a trade union activist full-time. At the same time, he was elected vice-chairman of the Surabaya office of the Indies Social Democratic Association (ISDV), which was to become the Indonesian Communist Party or PKI.

By 1918 he was a member of the central leadership of Sarekat Islam (SI), then the dominant nationalist political organization in the Dutch East Indies. In 23 May 1920, the Communist Party of Indonesia (originally the Partai Komunis Hindia, changed to ‘Indonesia’ a few months later) was founded after the deportation of the Dutch founders of the ISDV. Semaun became its first chairman. The PKI initially was a part of Sarekat Islam, but political differences over the role of class struggle and of Islam in nationalism between Semaun’s PKI and the rest of SI led to an organizational split. At the end of that year he left Indonesia for Moscow, and Tan Malaka replaced him as chairman. Upon his return in May 1922, he regained the chairmanship and tried, with limited success, to restore PKI influence over the sprawling SI organization.

In 1923 VSTP, the railway union, organized a general strike. It was soon crushed by the Dutch government, and Semaun was exiled from the Indies. He returned to the Soviet Union, where he was to remain for more than thirty years. He remained involved as a nationalist activist on a limited basis, speaking a few times to Perhimpunan Indonesia, a Netherlands-based organization of Indonesian students. He also studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East for a time. He travelled extensively in Europe, and played a role in leadership in Tajikistan in the Soviet era. He wrote a novel, Hikayat Kadirun, which combined communist and Islamic ideals, and produced a number of pamphlets and newspaper articles.

Upon his return to Indonesia after its independence, Semaun moved to Jakarta, where from 1959 to 1961 he served on a government advisory board. He was rejected by the new leadership of the PKI, and was affiliated to the Murba Party (Proletarian Party), which was opposed to the PKI. He also taught economics at Universitas Padjadjaran in Bandung. He died in Jakarta in 1971.

[2]

Raden Darsono Notosudirdjo (1897 Pati, Dutch East Indies – 1976 Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia). Darsono was converted to the cause of socialism when he attended the trial of Henk Sneevliet. He was impressed that a Dutch person would be willing to lose everything in order to side with the Indonesian people. He became a member of the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging and became secretary of the Semarang branch in 1918.

The Sarekat Islam (Malay: Islamic Union) was the first mass organization of Indigenous people in the Indies, who organized themselves loosely around the identity of Islam. But the organization contained quite a lot of ideological diversity, with Islamic nationalism (led by Cokroaminoto, Agus Salim and Abdul Muis), communists (led by Semaoen, Darsono and Alimin), and a synthesis of the two by Haji Misbach. In 1918, Darsono became a paid propagandist for the Sarekat Islam and became well known for his tireless effort to drive that organization to the left. Although the leaders of the “Central Sarekat Islam” based in Batavia (Jakarta) were skeptical of the move towards communism, they appointed Semaoen to their board as well as making Darsono propagandist. For this the central organization tried to make a deal with them to not publicly split with the organization or propagandize against them. During this time he was skeptical of the Insulinde party which had been founded by E.F.E. Douwes Dekker, Tjipto Mangoenkoesoemo and Soewardi Soerjaningrat. He expressed in meetings and articles that he believed that party mainly represented Indo people and that if they came to power they would relegate native Indonesians to a subservient position.

In May 1920, Semaoen refounded the ISDV as the Partai Komunis di Hindia (Malay: Communist Party in the Indies), which 9 months later would be renamed the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI). At that time Darsono was still in prison in Surabaya. In October 1920 the Semarang wing of the Sarekat Islam, and Darsono in particular, came into conflict with the central group of the organization in Batavia (Jakarta). Darsono was accused of breaking the truce with the central Sarekat Islam that had been agreed upon in 1917.

From 1921-23, Darsono left the Indies to travel through Siberia to Western Europe. During that trip he represented the PKI at the third Congress of the Comintern in Moscow. After that he worked for the Comintern in Berlin. He also spoke at a congress of the Dutch Dutch Communist Party in Groningen in 1921. In that speech he called for closer collaboration between the Dutch and Indonesian communist parties in the interest of reducing racial hatred. Darsono returned to Moscow in 1922. While he was abroad the Dutch authorities in the Indies discussed that he should be treated similarly to Semaoen and not allowed to reenter the colony when he came back from Europe. However, he did manage to reenter the Indies a year later.

In 1923 the Semarang authorities and the Governor General debated whether Darsono and Semaoen should be deported from the Indies, but decided against it for the time being. Although they were aggressively organizing strikes and spreading the communist message, the authorities thought that deporting them might not change anything. During this time, Darsono was relatively moderate as a communist compared to Semaoen, in that he did not believe in the use of bombings, terror or other methods. Darsono was finally arrested in 1925 and expelled from the Indies in 1926 If he was a more moderate figure, with him and the other PKI founders gone, the party became far more radical. The ill-fated 1926 PKI revolt happened while he and Semaoen were out of the country, and even though they tried to negotiate on the Indonesian communists’ behalf with the Soviet party, they were increasingly out of touch and unable to be of help from where they were.

He returned to the Soviet Union via Singapore and China; under the pseudonym of Samin, he worked for the Comintern for a number of years. He was even elected as an alternate member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International in 1928. In 1929 he also ran for office on the Dutch Communist Party list. However, he was expelled from the Comintern in 1931. Darsono was still in Berlin in 1935 when the Nuremberg Laws were passed. At this time many communists fled Germany, but he was unable to escape for a time, and so he left his son Alam Darsono to stay with Bran Bleekrode, a Jewish violinist living in Amsterdam whose cousin Bram Bleekrode was organizing places to stay for communists fleeing Germany. However, Darsono was apparently able to rejoin his son in Amsterdam later in 1935, where he stayed for a number of years.

Upon Indonesia’s independence from the Netherlands, Darsono finally returned to the country in 1950, after twenty years of being barred from entry. He broke with his previous communist views and became an advisor at the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs until 1960. Darsono died in Semarang in 1976.

[3]

Henk Sneevliet (1883 Rotterdam, The Netherlands – 1942 Leusden, The Netherlands).

He became a member of the Social Democratic Workers Party (SDAP) as well as the Dutch Association of Railway and Tramway Employees (NV) in 1902. From 1906, Sneevliet was active for the SDAP in Zwolle, where he became the first social democrat city council member in the elections of 1907.

Sneevliet was very active in the NV and was elected to the union’s executive committee in 1906. In 1909 he was tapped as vice-chairman of the union and named as editor-in-chief of the union’s official journal. He became chairman of the union in 1911. Sneevliet, as a committed socialist and militant trade unionist, was strongly supportive of an international seamen’s strike which was called in 1911 and was disgruntled by the failure of his union and political party to support the campaign. As a result, he resigned from both organizations, joining instead the more radical Social Democratic Party of the Netherlands (forerunner of the Dutch Communist Party) and writing for the Marxist magazine De Nieuwe Tijd (The New Time).

Sneevliet’s alienation strengthened him in his decision to leave the Netherlands for the Dutch East Indies. Sneevliet lived in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) from 1913 until 1918, where he quickly became active in the struggle against Dutch colonial rule. In 1914, he was a co-founder of the Indies Social Democratic Association (ISDV), in which both Dutch and Indonesian people were active. He also returned to union work, becoming a member of the Vereeniging van Spoor- en Tramwegpersoneel, a railway union which was unique in having both Dutch and Indonesian members. Thanks to his experience as a union leader, he soon managed to turn this still fairly moderate union into a more modern and aggressive union, with a majority of Indonesian members. This union later formed the base for the Indonesian communist movement.

ISDV was strictly anti-capitalist and agitated against the Dutch colonial regime and the privileged Indonesian elites. This led to much resistance against the ISDV and Sneevliet himself, from conservative circles and from the more moderate SDAP. In 1916 therefore he left the SDAP and joined the SDP, the predecessor of the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN). After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Sneevliet’s radicalism gained enough support amongst both the Indonesian population as well as Dutch soldiers and especially sailors that the Dutch authorities got nervous. Sneevliet was therefore forced to leave the Dutch East Indies in 1918. ISDV was repressed by the Dutch colonial authorities.

Back in the Netherlands, Sneevliet became active in the fledgling Communist movement, becoming a salaried official of the party’s National Labor Secretariat (NAS) and helping to organize a major transportation strike in 1920. The same year he was also present at the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow as a representative of the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), which was the successor to Sneevliet’s ISDV. There Sneevliet (using the pseudonym Maring) was elected a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International. V.I. Lenin was impressed enough by him to send him as a Comintern representative to China. Sneevliet lived in China from 1921 to 1923 and was present at the founding congress of the Chinese Communist Party in July 1921. Sneevliet was an advocate of cooperation with the non-Communist nationalist Kuomintang, headed by Sun Yat-sen, with whom he had personally established contact on behalf of the Comintern. Early in 1924 Sneevliet returned to Moscow, his tenure as a Comintern representative to China at an end.

Sneevliet returned to the Netherlands from Moscow in 1924 to assume the position of secretary of the National Labor Secretariat (NAS). He joined the executive committee of the Communist Party of Holland in 1925 but the two years were marked by worsening factional relations between Sneevliet and his co-thinkers and the bulk of the CPN leadership. The denouement came in 1927, when Sneevliet broke all ties with the CPH and the Comintern. In 1929 Sneevliet formed a new political party, the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP). This organization concentrated on national issues, gaining some successes in organizing the unemployed movement, strike actions, and the struggle against the rise of fascism.

He remained interested in Indonesian affairs and in 1933 was sentenced to five months imprisonment for his solidarity actions for the Dutch and Indonesian sailors who took part in the mutiny on “De Zeven Provinciën”, which was put down by an air bombardment in which twenty-three sailors were killed and which at the time aroused considerable passions in the Dutch public opinion. That same year, while still imprisoned, Sneevliet was elected a member of the Lower House of parliament, a position in which he remained until 1937. In August 1933 the RSP signed the “Declaration of the Four” along with the International Communist League, led by Leon Trotsky, the OSP and the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany. This declaration was intended as a step towards a new 4th International of revolutionary socialist parties.

The worsening political climate both abroad and nationally and the constant struggle against both the communist and social democratic parties, as well as government interference, took a heavy toll on Sneevliet and his small organization, however. When war broke out on 10 May 1940, Sneevliet immediately dissolved the RSAP. Some months later with Willem Dolleman and Ab Menist, he founded a resistance group against the German occupation, the Marx-Lenin-Luxemburg-Front (MLL-Front). This was largely engaged in producing propaganda for socialism and opposing the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and as such was heavily involved with the February strike of 1941.

As a known Communist, Sneevliet had to go into hiding even before he started his resistance activities. In the underground he edited a clandestine newspaper called Spartakus and took part in other activities. For two years he managed to keep out of the hands of the Nazis, but in April 1942 they finally arrested him and the rest of the MLL-Front leadership. Their execution took place just outside Kamp Amersfoort on 12 April 1942. It was reported that they went to their deaths singing “The Internationale”.

[4]

Adolf Baars (1892 Amsterdam, The Netherlands – 1944 Auschwitz concentration camp, Oświęcim, German-occupied Poland). He studied to become a Civil engineer in Delft, graduating in 1914. The college in Delft was a hotbed of student radicalism, and during his time there he joined the Amsterdam chapter of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party.

In 1914 Baars and his wife left the Netherlands for the Dutch East Indies, and Baars took up a post as an engineer in the state railway company (Staatsspoorwegen op Java) in Batavia (Jakarta) in early 1915. In December 1915 he left that position to become a teacher at the Koningin Emmaschool, a technical school in Surabaya. One student of his during this time was Sukarno, the future independence leader and first president of Indonesia. In the Indies, Baars soon became active in the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging (Dutch: Indies Social Democratic Association), or ISDV, and in the fall of 1915 joined the editorial board of its new party newspaper, Het Vrije Woord, alongside Henk Sneevliet and D.J.A. Westerveld. The paper was one of the only Dutch papers in the Indies to have earned the respect of many Indonesians involved in the Indonesian National Awakening, first because it denounced the arrest of the radical Mas Marco in 1916, and then because it publicly opposed the Indië Weerbar campaign to establish a ‘native’ army in the Indies.

Unlike many European socialists in the Indies, Baars worked hard to learn Malay and Javanese and used this knowledge to involve himself in Indonesian nationalist politics. Thus in April 1917 he helped found another newspaper, Soeara Merdika (Malay: Voice of freedom) with Semaun, Baars and Noto-Widjojo as editors. Published twice a month, Soeara Merdika was aimed at the type of people who might read Het Vrije Woord but who could not read Dutch, and to spread Social Democratic ideals among Malay readers of the Indies. ‘The paper failed and ceased publication within its first year, but Baars and his allies launched another paper, Soeara Ra’jat (Malay: People’s Voice), in March 1918.

By October 1917 the colonial government tired of his political agitation and honorably discharged him from his teaching job in Surabaya. The final straw was when, in August 1917, he had been giving a speech in Malay at an ISDV meeting and called the colonial government busuk (Malay: rotten), and when confronted by his superiors later, did not convince them that he was repentant. The firing was widely covered in the Dutch press of the Indies; the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad stated that Baars had defied the Government until his dismissal, so there was no need to feel sorry for him, and that he had in addition made “disgraceful” attacks on the education system in Het Vrije Woord. However, the Dutch-Indies Teacher’s Union (NIOG), in its January 1918 meeting, determined that he had been unfairly fired and proposed to give him financial support, although in the end none was given. Their declaration stated that a teacher should be able to act like any other citizen, and if his speech crossed a line into criminal sedition, it should be a matter for the police, not his employer. He was eventually offered a municipal engineering job by the mayor of Semarang, who was also a Social Democrat; this enraged the conservative newspapers in the Indies, such as De Preangerbode and Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië.

Because the ISDV was mainly an urban party, Baars and others within the movement supported the creation of rural or agrarian organizations. In 1917 this was attempted with Porojitno, which meant to organize peasants and unskilled laborers, and in early 1918 this was reorganized as the Perhimpunan Kaoem Boeroeh dan Tani (Malay: Workers’ and Peasants’ Association) or PKBT. Baars played a major role in it at first, although by 1919 it was reorganized again and came more solidly under the leadership of Haji Misbach in Surakarta. He also helped found an Indonesian socialist group in Surabaya in 1917 called the Sama Rata Hindia Bergerak (Malay: Equality Indonesia in Motion) which soon grew to match the ISDV in size. Those types of organizing efforts can be explained by Baars’ comments after the 1918 Sarekat Islam congress; he noted that the SI movement was still dominated by religious and nationalist elements, and hence he believed that separate organizations were necessary where members could be openly socialist and push for the SI to gradually take on a socialist character as well. Baars was very inspired by the events of the October Revolution and other revolutionary events in Europe. Baars became chairman of the ISDV in 1917, a position he held until 1919. The ISDV began to organize soldiers and sailors in the Indies on the Soviet example, and managed to recruit over 3000 by the end of 1917.

In early 1919, after authorities deported his ally Sneevliet from the Indies, Baars left voluntarily and returned to the Netherlands. The government would soon deport most of the other European ISDV members in the Indies, leaving the organization in the hands of Indonesians such as Semaun and Darsono. However, Baars did not have much employment or political success in the Netherlands and returned to the Indies in early 1920, once again taking up the engineering position he had been offered in Semarang. Upon his return to the Indies he was much more vocally opposed to the Indonesian nationalist movement, saying that nationalism and patriotism were the opponents of socialism.

At the ISDV’s annual meeting in May 1920, Baars was present and supported the proposal to rename the party to Perserikatan Kommunist di India (Malay: Communist union in the Indies). He wanted the party to avoid Revisionist tendencies and ally itself more explicitly with the Comintern. The motion was successful and the party was renamed. Het Vrije Woord now became the Dutch language organ of the renamed party, with Baars and P. Bergsma as editors, but due to the expulsion of many European socialists from the Indies, it apparently only had 40 subscribers by this time.

In May 1921 the colonial government finally tired of his activities and detained Baars, expelling him from the Indies on the basis of the destabilizing influence of his communist propaganda work. His recent articles in Het Vrije Woord were also cited as reasons, including one protesting the arrest of a PKI member and another describing the German counter-revolution. The Semarang municipal council, which he still worked for, objected on the basis that he had never broken any of the laws on propaganda and political organizing—he had limited himself to teaching and philosophical political writings—but that the government had ignored the law and taken advantage of its “extraordinary right” (exhorbitante rechten) to nonetheless deport him. Semaun, Baars’ longtime ally, spoke up at the same council meeting and stated that Baars’ expulsion had shocked members of their party, because of how diligently he had stayed within the bounds of the law and sought to avoid offense to anyone in recent years.

In May 1921 Baars and Sneevliet met in Singapore with Darsono and sailed to Shanghai, from where Baars and Sneevliet took the train to Moscow to attend the 3rd World Congress of the Comintern. Baars ended up resettling in the Soviet Union with Onok Sawina, becoming an engineer at the Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony in Siberia. There he came into close contact with other Dutch communists who were working in the colony, such as Sebalt Justinus Rutgers and Thomas Antonie Struik. It was later alleged in the Malay press in the Indies that he separated from his wife as early as 1922 and that she was living near Leningrad. In addition to his engineering work, he became a spokesman for the colony and worked for a time as its representative in Berlin. In 1927 he worked in the blast furnaces in Stalino (now Donetsk). However, he became disillusioned with communism and left the Soviet Union for the Netherlands at the end of 1927.

Upon his return to the Netherlands, Baars started publishing books about economics from 1928 onwards. However, the book that caused the greatest stir was his 1928 Sowjet-Rusland in de practijk: Indië tot leering (Dutch: Soviet Russia in Practice: Lessons to Indonesia). In the book, which was widely publicized in the conservative Dutch press of the Indies, he maintained that he still sympathized with the colonized peoples of the Indies, but that after years of working in the USSR, he no longer though the Soviet system had the capability to emancipate them. He wrote that foreign delegates in the USSR like his former allies Semaun and Darsono had very limited social circles; they worked in an office, received foreign letters and press clippings, and lived in a hotel, knowing little about the country they were living in. These letters he sent to the Indies Dutch press summarizing his book were translated into Malay, Javanese and Sundanese by the government-funded publishing house Kantoor voor de Volkslectuur (Balai Pustaka), in the hopes that it would turn readers away from communism.

A full-length book translation was even proposed but it is unclear if the translation that eventually came out received government funding or not. Baars’ allegations about life in the USSR were received with somewhat more skepticism in the Malay press in the Indies. The Bintang Timoer speculated that he may have published it as ‘revenge’ for his poor treatment by the Soviets and that it was difficult to verify. Other Malay papers, such as Abdul Muis’s Kaoem Moeda, saw a benefit to publishing it, since it might lead people back from the “darkness” of communism.

In the 1930s, Baars worked at the Netherlands Economic Institute in Rotterdam for some time. In 1937 he officially changed his name to Adolf, the name he had gone by for most of his life. According to historian Ruth McVey, Baars became a supporter of Fascism in his final years. On May 9, 1940, the day before the German invasion of Holland, Baars divorced his third wife, Aleida Lansink. During the Second World War, Baars was deported to Auschwitz concentration camp, where he was killed on March 6, 1944.

[5]

In 1960, Sukarno introduced “Nasakom”: an abbreviation of nasionalism (nationalism), agama (religion) and komunism (communism). This was intended to satisfy the three main factions in Indonesian politics: the military, Islamic groups and the communists. With the support of the military, he proclaimed “guided democracy” and proposed a cabinet representing all major political parties (including the Communist Party of Indonesia, although the latter never received functional cabinet posts).

[6]

In October 1965 in Indonesia, Suharto, a powerful Indonesian military leader, accused the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) of organizing a brutal coup attempt, following the kidnapping and murder of six senior army officers. In the months that followed, he oversaw the systematic extermination of as many as one million Indonesians because of ties to the party, or simply because they were accused of harboring leftist sympathies. He then took power and ruled, with American support, until 1998.

“How do we shape the world?” That is the question that is always on Michiel Huijben’s mind, a visual artist whose work centres around how architecture and space influence our lives. Huijben studied in Breda, Amsterdam and London, and currently lives in Rotterdam. He explains how he sees the world: “I am trained as a fine artist, but I look at everything through an architectural lens.” The question of space in a broader sense inspired Huijben to dive into the Open Archief in search for the history of the social function of public places, such as the Malieveld in Den Haag.

When Huijben used to focus on space in his artistic works, he would do so intuitively. As he reflects back on his works he says: “At one point I realized that the intuitive approach I used was not a choice. It was all I had.” That realization came when Huijben read the book Eccentric Spaces by Robert Harbison. “That book was a real eye-opener,” he declares, “Harbison discussed architecture in a different way than I did, connecting it to imagination and fiction. I started researching him, and when I discovered that he found a course in architectural theory in London, I decided to do that.”