In his article Of Other Spaces, Michel Foucault talks about certain places in cultures, that exist and are formed in the very founding of society, something like counter-sites, effectively enacted utopias, within which all the other sites are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. He calls them heterotopias. As opposed to utopias, that are, effectively, sites with no real place, the location of heterotopias can be indicated in reality. Describing different types of heterotopias, Foucault speaks about libraries, museums and archives as spaces “in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit. […] Opposite these heterotopias, there are those linked, on the contrary, to time in its most fleeting, transitory, precarious aspect, to time in the mode of the festival.”[1] An archive and a carnival can be seen as representations of these two different types of heterotopias, in their contrasting relation to time. One of them is an immobile place of perpetually and indefinitely accumulating time, whereas the other one can only exist in its fleeting temporality. But both of them are microcosms, containing a world within a world, mirroring, inverting and subverting the ‘outside’ reality.

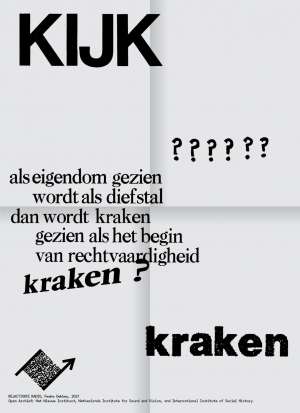

Archives are often seen as carefully curated collections, metaphors for a collective consciousness. But they also can be seen as ‘cabinets of curiosities’, where through systems of organisation, certain perceptual frameworks are revealed, and worldviews are constructed. They substantially contribute to the creation of meaning and knowledge, they project a certain accumulated worldview onto society and the future, becoming its foundation. In order to understand an archive better, we can ask questions like: Why does this archive exist? Why does it contain this item rather than another? And what is missing from the archive? After all, who decides what goes into an archive? Historically these decisions have been gendered and centred on particular ideas about what and who matters in history. Archives are always partial and biased, never complete. They are epistemological moments, rather than passive collections. The moment the objects are being archived they become frozen in a fixed position and order. As Jacques Derrida famously said in Archive Fever: “[The] technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future.”[2] Memory is not a storage, it requires constant reflection to keep it alive. Power is at the centre of archival work: it has the power to retain, the power to discard, the power to partially shape what is remembered and how. What do institutions remember? What do they forget? Archives are filled with gaps and silences. Being archived can prove your existence, but can your absence from the archive indicate the opposite? Another question that can be asked is, can archives be a space for envisioning a different future?

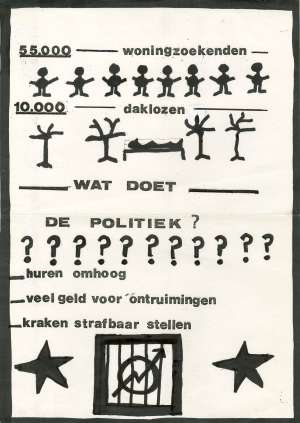

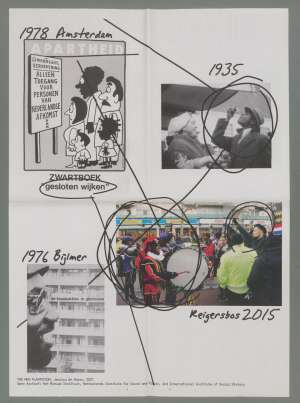

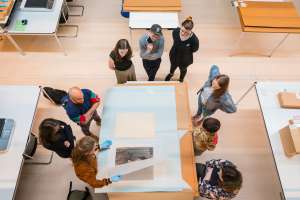

Archives undoubtedly have a strong influence on the future, as a resource for knowledge production and projection of certain worldviews. They also often contain a repository of possible futures, of yet to materialise realities, “historical alternatives that haunt a given society”[3] in the form of utopian ideas, political imaginaries, alternative communities, technological innovations and artistic and architectural projects. They can all be seen as a manifestation of different forms of imagination. Working with the archives of the International Institute of Social History (IISG), Beeld en Geluid and Nieuwe Instituut, I was interested to reflect on how manifestation of these ‘haunting futures’ influence construction of social reality and cultural and political thought. Who has the right to imagine them? And is it at all possible to think about future outside of anxiety that surrounds it?

The myth of the future, as a cultural construct built around the notion of progress, spacial idea of expansion, advancement of economy and knowledge, is rooted in the early modern period and the emergence of modern capitalism and the colonial era. The current state of a disillusionment in the future and the inability to imagine an alternative to capitalism, can be understood as a cultural logic of advanced capitalism. The future doesn’t appear to be an object of choice and a collective conscious action, but an inevitable catastrophe. To quote Rosi Braidotti: “The contemporary imaginary is impoverished and unable to think about difference outside of frame of deep anxiety.”[4] The continuous war against imagination, which according to David Graeber, “is the only war capitalists have managed to win,”[5] led to the widespread death of political imagination. And the bureaucratic and financial apparatus, created to general perpetual hopelessness, destroys any sense of possible alternative futures and shreds human imagination.

When I first started my research in the archives, I began to explore how imagination was expressed in them. In my previous research I was interested in the history of imagination as an internal sense, playing a key role in mental function, and having the power to influence reality, its political potential and subsequent censorship and control, as well as its relation to vision and representation. Working with the archives, I wanted to reflect on the power of imagination and its political dimension, on the right to imagine in the context of contemporary lack of social and political imagination, and the inability to envision a world, different from the one we currently live in. I wanted to observe the connection between memory and imagination, past and future, as they are embodied in the archives.

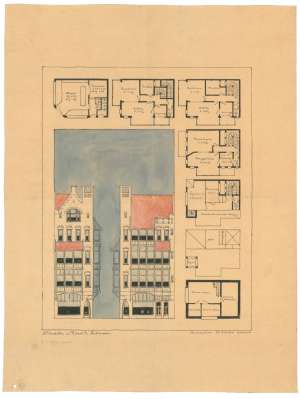

I began to explore the utopian collection of IISG, in order to reflect on the relationship between utopian imaginaries and social movements. At the same time, I was also looking for different manifestations of ‘imagination’ and ‘future’ through examples of technological innovation, science fiction narratives, and modernist projects. When I came across documentation of carnival celebrations in the Netherlands in the archive of Beeld en Geluid, I found carnival to be a perfect metaphor for an enacted utopia and an expression of social and political imagination. Eventually, these different elements and thoughts came together in the film, in a juxtaposition of well-known political utopian ideas, modernist utopian architectural dreams and more marginal feminist utopian narratives.

Utopia.

Utopias afford consolation: although they have no real locality there is nevertheless a fantastic, untroubled region in which they are able to unfold; they open up cities with vast avenues, superbly planted gardens, countries where life is easy, even though the road to them is chimerical.

— The Order of Things, Michel Foucault, 1966

The power and impact various utopias had and are still having on reality is vast. There is a clear link between utopian ideas and social movements, and the collection of IISG is a great illustration of that connection. Their utopian collection contains books about imaginary travels, utopian communities and futuristic visions. It includes “contemporary editions spanning centuries of utopian thought and ranging from a very early reprint of More’s Utopia (1518) to works by Fourier, Saint-Simon, Cabet, Proudhon, and Owen.”[6] As one of the treasures of the collection, in a vitrine in the heart of the building, Thomas More’s third edition of Utopia is proudly displayed next to the manuscript of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. The works of utopian thinkers inspired social movements, utopian experiments and alternative communities. Is there still potential in utopian thinking? Can it have a politically energising perspective? Can it be a radical act of philosophical speculation? One undoubtedly positive element in utopia, is that through it, the reader gets infected with the possibility of an alternative. Utopian vision of a better society relies on the engaging of imagination to see the possibilities. There is a power in seeing something that you can’t ‘unsee’. It makes you understand that the alternative is possible. The ‘naturalness’ of the world gets disrupted.

Utopian ideas are present in myths, religions and imaginaries of many cultures. But the concept of utopia is considered to be a by-product of Western modernity, with Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) being its starting point. This book is “almost exactly contemporaneous with most of the innovations that have seemed to define modernity (conquest of the New World, Machiavelli and modern politics, Ariosto and modern literature, Luther and modern consciousness, printing and the modern public sphere)”.[7] Throughout the time, utopia went through multiple transformations, and the relationship towards it kept changing. In each utopian narrative historical conditions of possibilities of these peculiar fantasies were revealed.

The questions about the practical-political value of utopian thinking and the identification between socialism and utopia, continue to be unresolved. The classical criticism of the utopian impulse is that it is impossibly distant. Utopia is anywhere but here and now, it is alternatively the ‘good place’ (‘eutopos’) and ‘no place’ (‘outopos’). But more importantly from its very origin it is based on brutality and coerced from above. To quote Ursula K Le Guin: “Every utopia since Utopia has also been, clearly or obscurely, actually or possibly, in the author’s or in the readers’ judgment, both a good place and a bad one. Every utopia contains a dystopia, every dystopia contains a utopia.”[8] Like in the case of Thomas More’s Utopia itself, which on the one hand denounced private property and advocated a form of communism, on the other hand was originally built by a tyrant Utopus on colonisation of the “uncivilised inhabitants” and creating an artificial island by “bringing the sea around them”.[9]

“There were good reasons to distrust and even dismiss the term ‘utopian’, although […] the main problem was not idealism and futurism, but rather the term’s deeply racialised historiography and narrow set of literary, aesthetic, philosophical, historical and sociological references.”[10] Feminist utopian and science fiction writers embraced the potential of the utopian genre, even though feminist utopias were quickly dismissed and moved to the margins of the discussion, into its own subfield, as a result of the the effects of structural violence on the imagination. Feminists were critical of closed-ended, top-down utopias depicting static perfection with no room for development, that rely on rigid hierarchies and coercion to maintain this order. Instead of projecting a totalising idea, feminist utopian speculative fiction, deals with imagining the future, building on the critique of the present and past. This type of the utopian writing is often also referred to as SF, which, as Donna Haraway describes it, “is that potent material-semiotic sign for the riches of speculative fabulation, speculative feminism, science fiction, speculative fiction, science fact, science fantasy—and, […], string figures. In looping threads and relays of patterning, this SF practice is a model for worlding…”[11]

Carnival.

I believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience which would be the mirror.

— Of Other Spaces, Michel Foucault, 1986

Carnivals, as much as mirrors, are real spaces that contain a ‘parallel’ world. They are enacted utopias, that can only exist in their fleeting temporality. Following the template of utopia and dystopia, heterotopia (Ancient Greek: hetero - other, another, different; topos - place, which can be translated as ‘other, different place’ or ‘a place of differences’) is a parallel space mirroring and yet upsetting what is outside. Heterotopias can be seen as spaces that make room for something politically experimental. They are spaces of and for the imagination. Foucault calls for a society with many heterotopias, not only as a space with several places of/for the affirmation of difference, but also as a means of escape from authoritarianism and repression. When I came across videos of documentations of carnivals, I saw them as a great example of a heterotopia—a microcosm, a space where imagination seemingly runs wild… A ‘reimagined’ space that at the same time allows for imagination to manifest itself. A bodily expression of a utopia.

Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy ‘syntax’ in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to ‘hold together’.

— The Order of Things, Michel Foucault, 1966

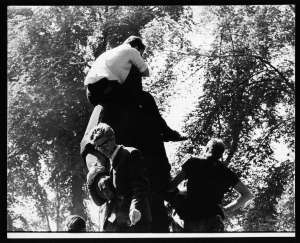

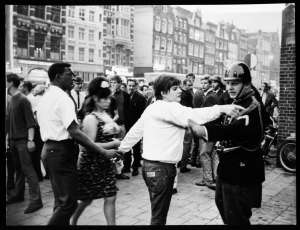

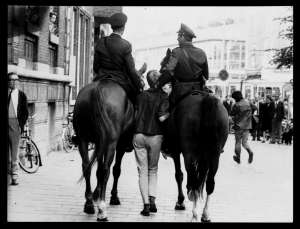

Early on, carnivals were recognised as having potential to be one of those ‘disturbing’ spaces, where norms and categories could be questioned and challenged, and status quo suspended. The theory of carnival as a transgressive act of political resistance is generally said to have been pioneered by the Soviet structuralist Mikhail Bakhtin. In his study of Rabelais’s work, Bakhtin presented medieval and Renaissance carnival as a festive critique, through the inversion of binary semiotic oppositions, of ‘high culture’. This analysis contributed to carnival being conceptualised as a ritual of rebellion. “To Bakhtin, however, carnival did not simply consist in the deconstruction of dominant culture. It also eliminated barriers among people created by hierarchies, replacing them with a vision of mutual cooperation and equality. […] On a psychological level, it generated intense feelings of immanence and unity—of being part of a historically uninterrupted process of becoming. It was a lived, bodily utopianism, distinct from the utopias deriving from abstract thought, a ‘bodily participation in the potentiality of another world’”.[12] Bakhtin’s work was foundational for the field of ‘carnival studies’, which emerged in the 1970s as a combination of cultural history, anthropology, and sociology.

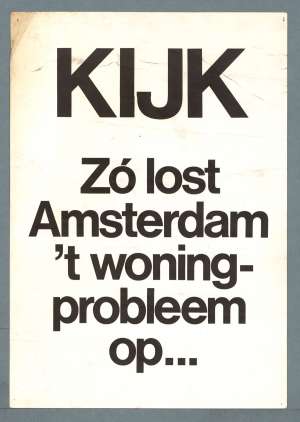

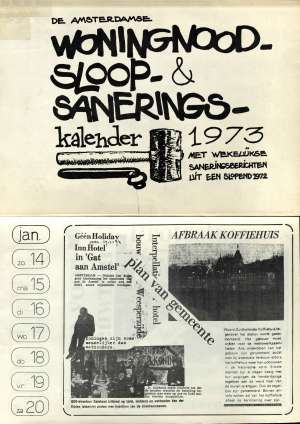

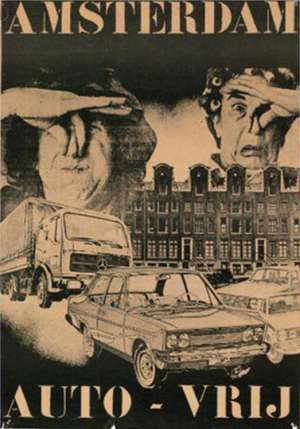

Carnival parades with large floats are a superabundance of symbols and meanings, a spectacle, an exhibition, a flow of monsters, fanciful characters and jokers. Many parade themes tell a visual story of recent events. It was also a custom during carnival that the ruling class would be mocked using masks and disguises. The combination of political protest and colourful party exploits the ambivalent position of carnival, between aesthetics and politics. Throughout the history of the carnival in the Netherlands, there were various moments of censorship, when either the church or the state were trying to prohibit it altogether or censor certain topics and representations. A new morality was tested, to see what was allowed. And while certain subversive types of behaviour were allowed, the total freedom and anarchy were not welcome.

“Carnival spirit with its freedom, its utopian character oriented toward the future, was gradually transformed into a mere holiday mood,” Bakhtin concluded.[13]

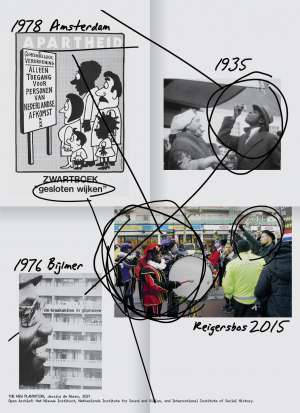

“By the mid-nineteenth century the change was complete: carnival culture had been relegated to the sentimental realm of folkloristic survivals.”[14] As a result of domestication, commercialization, political co-optation, aestheticization, traditionalization and institutionalisation, carnival has lost its political potential having transformed into a space of escapist fun in the form of mainstream entertainment. It has transformed into a space that reproduces hierarchies, power structures, and misrepresentations of the world they mirror, where strong sets of guarded traditions and practices often stay exclusionary, perpetuating racism and gender stereotypes.[15]

New Babylon.

Daria Kiseleva, Haunting Futures, 2022.

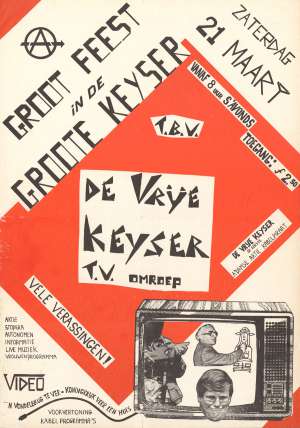

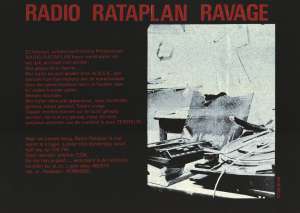

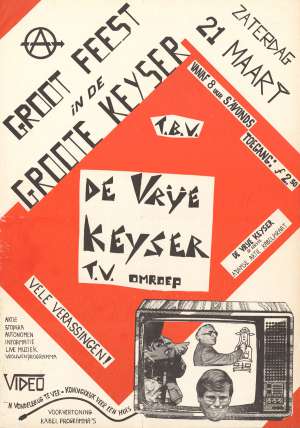

The question if the nature of carnival is inherently transformative and subversive, or fundamentally conservative, divides the opinions of the scholars. Some researches see carnivals as a form of social control, arguing that its ritualised, periodic nature serves as a mechanism to dissipate revolutionary energy and maintain the status quo. Others see a possibility of carnivals to create a space for renegotiating and resisting hegemony. The rebellious potential of carnivalesque—“as a medium of emancipation and a catalyst for civil disobedience”[16]—was embraced as a cultural practice and instrumentalised during the protests by the global anarchist movement.

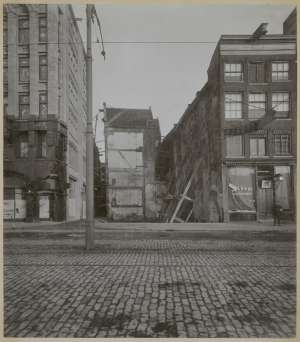

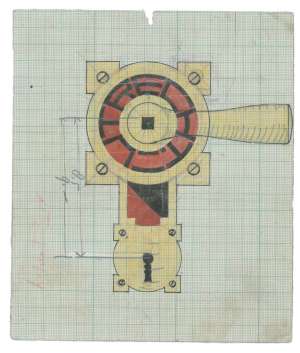

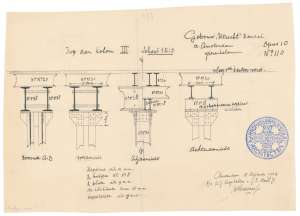

The element of carnivalesque was already previously used and advocated for, by the members of the Provo movement (1965-1967), as a way of provoking the authority through a playful action, in which uselessness and voluntary unemployment were contrasted with authoritarian morality. Carnivalesque, or a playful action, was also close to the philosophy of the dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhyus, whose “architectural science fiction”[17] project New Babylon (1956-1974), can be seen as an ultimate modernist utopia, based on an idea that it is possible to escape an unfree world by achieving full automation. Describing the future population as homo ludens, Constant imagined the world wide city of the future, in which the need to work is replaced by a nomadic life of creative play, a modern return to Eden. “Deeply rooted in the tradition of the avant-garde with the desire for the renewal of society, New Babylon offers a challenging proposal of a network of enormous multilevel interior spaces spreading so as to eventually cover the planet…”[18] Architecture and urban planning have always played a vital role in the utopian imagination. By the early modern period the promotion of city planning and the design of urban spaces became a means of creating and maintaining social control in utopian plans and fantasies. In More’s Utopia the world consists of uniform towns that are geometrically organised, creating an infrastructure that supports the discipline of the inhabitants. Idealised urban spaces are described in Francis Bacon’s description of Bensalem in New Atlantis (c. 1624), Charles Fourier’s phalanstère buildings and Robert Owen’s proposed communities of the early 19th century.

New Babylon contained in itself both an extreme artistic and architectural plan, and the element of carnivalesque, or playfulness, that formed his ideological vision of the construction of a ‘new man’—homo ludens. The utopian vision of liberation through play and creativity is manifested in a total abstract vision of one man, through homogenisation and elimination of differences. But New Babylon, isn’t a safe space, according to Constant. Instead it is a space of conflict. And the liberated through creativity homo luden is not liberated from aggressively and violence.

“Eventually, Constant foresaw the destructive part of his proposed environment, since the last of his drawings lay bare a site of violence and terror”.[19]

Imagination.

What revolutionaries do is to break existing frames to create new horizons of possibility, an act that then allows a radical restructuring of the social imagination. This is perhaps the one form of action that cannot, by definition, be institutionalized.

— Revolution in Reverse, David Graeber, 2011

This uniformizing ideal of progress, as it moved the western world away from nature, blinded us to the immanence of life. It also alienated us from the different futures that were not in line with the Enlightenment ideals. It is these alternative future scenarios that are becoming more feasible and necessary in the era of the Anthropocene, and which are emerging as new paths of becoming.

— Philosophy after nature, Rosi Braidotti, 2017

Imagination has long been a subject of philosophical debate and its power had been widely recognised. Studies in the history of imagination explore ideas about the physical force of imagination as it was understood in the early modern period. Imagination (or Phantasia) “lodged between sense perception (the realm of the objective) and memory or mind, or soul, processes perception”,[20] by means of images. Socrates likened the impression of images in the mind to imprinting seals in wax. In the period of early modernity images (in early natural science atlases) gained the power to stand for what they represented, becoming truthful records of their subjects. At the same time imagination started to be seen as one of the internal senses, playing a key role in mental function, according to the early modern medico-philosophical theories, and having the power to influence reality, forming an image-based model of cognition. Descartes attributed to imagination yet another role: an act of the will, that connected it to the practical, ethical and political dimensions of human life. It was understood that the inability to control imagination could amount to a threat to social order. What is produced in the imagination can be dangerous and subversive. Multiple thinkers warned against the dangers of imagination and the necessity to control it. Amongst them was Hobbes, who in his political treatise Leviathan (that is also often suggested to be a utopian work) posited that in order to “ensure social unity, peace and political stability, the sovereign must maintain his subjects in the state of ‘political sleep’, preventing any kind of new inputs from disturbing their imagination and by establishing a strict regime of censorship in order to combat and silence any alternative imaginaries”.[21]

An alternative understanding of imagination was proposed by Spinoza, for whom it consisted in the awareness of the bodies before us, and an individual was seen as a constitutively interdependent being, produced through and productive of its relations with other individuals. “… for Spinoza the life of the mind, and so of imaginative life, is also the life of the body. This is the first sense, then, in which imagination, as a way of thinking, is also a way of existing”.[22]

Drawing from Spinoza’s understanding of imagination, as a more embodied, relational and interdependent experience, imagination can be seen as a social praxis, as a continuous process of reinvention of the self “on a basis of what you hope you could become”,[23] and re-conceptualisation of normative categories and social, cultural and political constructs. Imagination is based in the present, drawing inspiration from past struggles and ‘alternative futures’ to work on the present, “actualising the virtual possibilities which have been frozen in the image of the past [24]. The tense that best expresses the power of the imagination is future perfect. This is the tense of the virtual sense of potential. Memories need imagination to empower the actualisation of virtual possibilities.

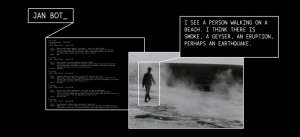

From this perspective I looked at the archives as repositories of possible futures of the past. In thinking about the future there is a danger of detaching oneself from the present. Therefore, Haunting Futures is rather speculating how to inhabit the troubled present, by engaging with these ‘haunting futures’, as opposed to the idealistic visions and modernist ideas, dreaming of creating a clean slate by means of destruction of the past. The film itself, just like the carnival, is a heterotopia, akin to a mirror, containing a real and a fictional image at the same time. It is both a science fiction horror and a documentary where the ghosts of the past and present come alive. It is in a constant flux, opposing the binary logic, creating a space of confusion and disrupting the possibility of a historicising logic.

- Of Other Spaces, Michel Foucault, Diacritics 16:1 (Spring 1986), 22-27.

- Archive Fever, Jacques Derrida (Éditions Galilée, 1995), 17.

- One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society, Herbert Marcuse (Beacon Press, 1964)

- Metamorphosis. Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming, Rosi Braidotti (Polity, 2002), 184.

- Revolution in Reverse. Essays on Politics, Violence, Art and Imagination, David Graeber (Autonomedia, 2011), 113.

- https://archief.socialhistory.org/en/collections/utopian-travels/utopianism (last accessed February 22, 2023)

- Archeologies of the future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, Fredric Jameson (Verso, 2005), 2.

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/nov/04/thomas-more-utopia-500-years-china-mieville-ursula-le-guin (last accessed February 22, 2023)

- Utopia, Tomas Moore (1516)

- Revolutionary Feminisms. Conversations on Collective Action and Radical Thought, edited by Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah (Verso, 2020), 186.

- SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far, Donna J. Haraway

https://adanewmedia.org/2013/11/issue3-haraway/ (last accessed February 22, 2023 - Godet, Aurélie. “Introduction: Behind the Masks, The Politics of Carnival.” Journal of Festive Studies 2, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 1–31. (https://doi.org/10.33823/jfs.2020.2.1.89)

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky

- Godet, Aurélie. “Introduction: Behind the Masks, The Politics of Carnival.” Journal of Festive Studies 2, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 1–31. (https://doi.org/10.33823/jfs.2020.2.1.89)

- The membership in the local carnival associations is usually secured by men, and women’s role extends only to administrative work or participation as Danzmariekes.

- Occupy Wall Street: Carnival Against Capital? Carnivalesque as Protest Sensibility, Claire Tancons (https://www.e-flux.com/journal/30/68148/occupy-wall-street-carnival-against-capital-carnivalesque-as-protest-sensibility/) (last accessed February 22, 2023)

- Constant, Le grand jeu a venir, Potlatch, no.30 (15 July 1959). Translated by Gerardo Denís as “The Great Game to Come” in Libero Andreotti and Xavier Costa, eds., Theory of the Derive and other Situationist Writings on the City (Barcelona: MACBA and ACTAR, 1996), p. 62-65. In Constant’s New Babylon. The hyper-architecture of desire the hyper-architecture of desire, Mark Wigley (1998), 13.

- The Activist Drawing. Retracing Situationist Architecture from Constant’s New Babylon to Beyond, ed. Catherine de Zegher and Mark Wigley (MIT Press, 2001)

- Ibid.

- Claudia Swan, Art, science and witchcraft in early modern Holland. Jacques Gheyn II (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 16.

- The Sleeping Subject: On the Use and Abuse of Imagination in Hobbes’s Leviathan, Avshalom M. Schwartz (Stanford University, 2020) https://brill.com/view/journals/hobs/33/2/article-p153_153.xml?language=en#ref_FN000002)

- The logic of imagination: a Spinozan critique of imaginative freedom, Amanda Parris (College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations, 2018), https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/2602018)

- Writing as a Nomadic Subject, R. Braidotti, Comparative Critical Studies, vol. 11, no. 2-3, (Edinburgh University Press, 2014)

- Ibid.

![(link: https://zoeken.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/nl/objecten/detail?q=trans&page=4&asset=16d043d5-c845-81af-e6dd-7be813be5251%3E text: Trans Europe Express [TEE] Modellen target: _blank), plaster model by Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (architect), Werkspoor (opdrachtgever), Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (maquettebouwer), 1953/1957. Objectnummer: MAQV591.03, Collectie Het Nieuwe Instituut.](https://www.openarchief.com/media/pages/blog/two-main-directions/206dd11d58-1563366616/e25db3aeb5daaaba2228f02ceedc6f4d94242a88f1ad8dc28ac39724d1559ce3-300x.jpg)

![(link: https://zoeken.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/nl/objecten/detail?q=trans&page=4&asset=16d043d5-c845-81af-e6dd-7be813be5251%3E text: Trans Europe Express [TEE] Modellen target: _blank), plaster model by Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (architect), Werkspoor (opdrachtgever), Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (maquettebouwer), 1953/1957. Objectnummer: MAQV591.03, Collectie Het Nieuwe Instituut.](https://www.openarchief.com/media/pages/blog/two-main-directions/206dd11d58-1563366616/e25db3aeb5daaaba2228f02ceedc6f4d94242a88f1ad8dc28ac39724d1559ce3-1800x.jpg)